You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘wreck divers’ tag.

Two summers ago, over watermelon mojitos, I met with Captain Rick Hake of Adventure Charter Boats, who shocked me with stories of violent storms and deadly shipwrecks in the Lakes’ waters.

“How many people, on average, do you think survived, per wreck?” he asked me.

“Twenty,” I flat-out guessed.

He smirked and shook his head of floppy hair. “One,” he said. “One person, per wreck. On average.”

I was working on a story for VITAL Source (today’s ThirdCoast Digest) and I had no idea lake wrecks were remarkable, let alone abundant, so Rick sent me off to work on my story with an armful of books, site maps and a list of phone numbers for other local wreck divers, some of them legendary. Even more surprising to me than the low rate of survival on Great Lakes wrecks was the fact that people actually get into the limb-numbing waters and stay in it for hours to hang out with some zebra mussel-covered boat frames, but of course, as any wreck diver will tell you, the Great Lakes offer some of the best diving in the world, because the wrecks are so well-preserved by the low temperatures on the lake beds and the lack of corrosive salt. Some divers still hunt for treasure, too, and although they are not legally allowed to take silver egg-cups, musical instruments or fine china from a wreck site, many of them do anyway, following that ageless law of the sea: “If I don’t take it, it’s just going to rot down there.”

After I turned in my story, my editor rewrote my headline and all of my subheads which, to his credit, were probably not great in the first place, BUT: to replace my anemic header copy, he chose quotes from the lyrics of the Gordon Lightfoot song “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald,” and I was livid.

“The Fitz sank in Lake Superior,” I told him. “This is a story about wrecks in Lake Michigan.”

“Yeah, but it’s the only Great Lakes shipwreck people know about,” he said. “And it’s a good song.”

People are still surprised to learn that the Edmund Fitzgerald, although it was the latest and largest Great Lakes shiprweck and the only one so far commemorated in a contemporary folk song, was not, by far, the deadliest disaster. Thousands of ships and more than a thousand lives have been lost on the lakes since Rene La Salle’s fur ship Le Griffon sank in Lake Huron in 1679, many of them killing hundreds of people. (La Salle himself was not on the boat; he took the voyage from Green Bay to Niagra by canoe.)

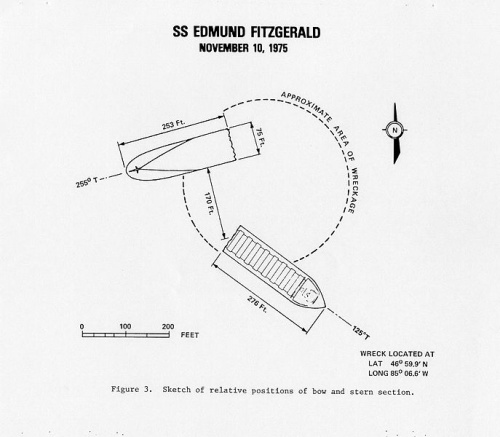

At 11 a.m. this Sunday, November 8, the Mariner’s Church in Detroit will hold its annual Great Lakes Memorial service in remembrance of the Edmund Fitzgerald (which sank on November 10, 1975, en route from northern Wisconsin to Zug Island, drowning all 29 men on board) and all of the lives lost on our inland seas.

The Mariner’s Church is the oldest structure on the riverfront, commissioned in 1842 by Julia Anderson, the widow of Colonel John Anderson, who commanded a regiment in the War of 1812. Julia specified a stone church that would last the ages and forever offer a free pew anywhere in the church to anyone who wanted to worship, especially sailors, who were marginalized in civil society at the time. Old Mariner’s also served as an important stop on the underground basement; refugees snuck through a tunnel in the basement to the waterfront and thereon across the river to Canada. (The Mariner’s Church website offers a thorough history with a great photo gallery recommended for further reading.)

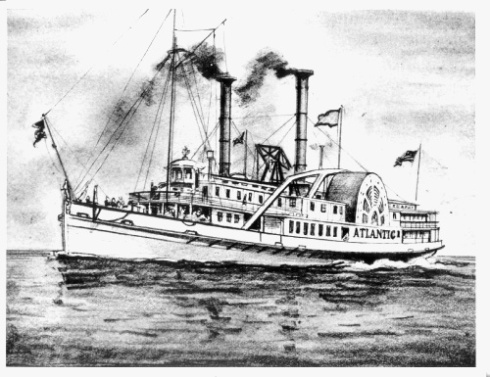

There are dozens of books about Great Lakes wrecks, published mostly by small regional presses and written largely in a swashbuckling narrative style that sacrifices historical detail for suspenseful flair. They’re delightful nonetheless, and since it’s worth remembering at least one fateful night that didn’t sink the Fitz, here’s an excerpt about the sinking of the sidewheel steamer Atlantic, which sank in Lake Erie en route from Detroit to Buffalo in 1852.

From Great Stories of the Great Lakes by Dwight Boyer (1966):

The Atlantic, back on her Detroit-Buffalo course after a stop at Erie, Pennsylvania, was steaming slowly through a heavy fog in the dark early-morning hours of August 19, 1852. Pacing the wheelhouse sleeplessly as the ship’s bell tolled out warning clangs at regular intervals, Captain J. Byron Pettey was grumbling to the wheelsman about the vessel’s overcrowded condition. There had been more than the normal complement of passengers at Detroit, about three hundred in all, and a great tonnage of freight. Despite this, the Atlantic was committed to stop at Erie to pick up two hundred Norwegian immigrants, bound for Quebec. But the captain had been obliged to leave seventy-five of them on the wharf — there just wasn’t room for them. as it was, those taken aboard were bedded down on the hurricane deck, on the forepeak of and in the companionways. Their trunks, boxes and bundles — their sole wordly possessions — were piled all over the ship. Adding to the Captain’s worries was $36,000 in American Express Company gold, reposing in the purser’s safe.

… There was a flurry of shouted orders, a hasty clamoring of steam whistles, a great clanking of metal as the ship’s big walking-beam engine thrashed violently astern and finally, a hollow rumbling as the Atlantic was rammed forward of the port wheel by the propeller steamer Ogdensburg!

Like two dogs that have tangled viciously but briefly and then backed of to survey the damage wrought, the ships drifted apart after the collision, neither, apparently, seriously holed. But minutes later a begrimed and frightened fireman sought out the Captain to report that the Atlantic was looding below with water spurting up through the engine-room gratings. Captain Pettey gave the “abandon ship” order and the crew began their orderly routine of lowering boats and assigning seats. But the terrified Norwegians, who understood no English, panicked at the shouted orders and began to jump overboard. By now the water had reached the fires and huge clouds of steam began spurting up from the skylights and companionways. In this eerie scene of disaster the Atlantic made her final plunge, leaving the surface of the lake cluttered with wreckage, trunks and drowning passengers … almost 300 people, many of them hapless immigrants, either went down with the ship or drowned while waiting rescue. The Atlantic went to the bottom some four miles off Long Point in 155 feet of water.